Adaptations of Freshwater Crayfish to Life in Flowing Rivers

We shall not consider the general adaptation for aquatic life found in the Crustacea generally, but only those features of the fresh water crayfish which adapt it for life in flowing rivers and in burrows. Crayfish has for long been a rich source of protein for most homes especially in developing countries where the cost of other protein sources such as milk, meat and eggs are quite expensive. Our understanding of the adaptation of crayfish to life in flowing rivers gives us an idea into how this organism has modified its behavioral pattern to ensure its survival.

The dull green color of crayfish is ideal camouflage for river water and coupled with its stealthy nocturnal movements, makes it a far from conspicuous animal. Its relative density is about 1.1, so that although it stays easily on the river bed, the great majority of its weight is supported by the water.

The freshwater crayfish is not particular about its food, but will scavenge any debris or attempt to capture smaller creatures swept by in the current. The rivers it inhabits contain relatively pure water, highly oxygenated and include sufficient calcium salts for impregnation of the skeleton. In a large crayfish these salts may amount to 15 per cent of the total weight of the exoskeleton.

The slow forward movement is indicative of the fact that it is not an active predator; that the food supply comes easily to it, while the rapid backward darting enables quick escape from danger, here, the versatility of the antennae is important.

As it is a freshwater animal, osmoregulation is a serious problem in this connexion, its blood pressure of 20 cm of water enables it to force fluid into the green gland.

A number of adaptations are to be found in its nervous system. The eyes can be both light and dark adapted. The giant fibres enable practically simultaneous transmission of stimuli to the muscles concerned in backward movement. There is a light detector it the last thoracic ganglion which guards against the danger of the backing into a burrow which has another entrance.

The whole reproductive process is highly adapted to life in flowing water. Though fertilization is external, the sperm are not liberated as swimming gametes; indeed they can scarcely be said to be liberated at all. They are carefully deposited in sticky masses on the female abdomen. This necessitates a special fertilization mechanism. The whole process of egg-laying, attachment of the eggs and young, is adaptive. Finally, the type of egg and consequent advanced stage of development at hatching, are also adaptation to secure survival of the young small larvae would be swept away and would not be able to find sufficient food In the rivers.

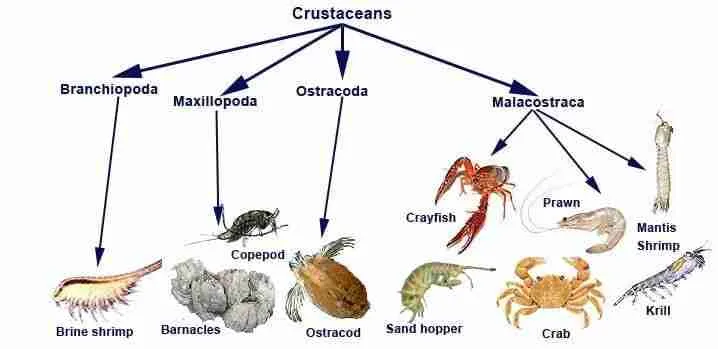

Classification

Phylum: Arthropoda

family: Astacidae [Potamobiidae]

Class: Crustacea

Genus: Astacus

Order: Decapoda

Species: Astacus fluviatilis, Astacus torrentium

Crustacea in order Decapod have five pairs of legs, each possessing endopodite only. There are usually three series of gills; podobranchs, arthobrachs and pleurobranchs. The thorax bears three pairs of maxillipeds. Members of the family Astacidae have the podobranchs partly united with epipodites and there are appendages present on the first abdominal segment of the male and usually also on the female. The genius Astacus is distinguished from other genera by details of body proportions and by small details in the appendages the various species are distinguished on matters of size and color.