4 Important Functions of the Mammalian Skin

The mammalian skin provides protection from various hazards; it is an excretory organ; it subserves temperature regulation and sensitivity, acts as a physical barrier and secretes important substances that help in insulation and protection.

Physical protection from damage is provided by stratum corneum and the fur of the mammalian skin, while the color gives some measure of camouflage. The hair traps a layer of air near the body surface and this acts as an insulating layer, preventing excessive loss of heat. Thickness of the adipose tissue is another important factor in this connexion, though in the rabbit is is not of great significance. In the mammals which have become secondary aquatic, the blubber is of great importance.

The sweat is, to some extent, an excretory product. It consists of about 95 per cent water, 2 per cent of dissolved salts, mainly sodium chloride, a small quantity of urea, and about 3 per cent of carbon dioxide, all by weight. It is passed from the capillaries into the carbon of the tubules and secreted by them into the lumen. General, the sweat is evaporated, but in conditions of high temperature or grate muscular activity, it may run off the body as fluid.

Regulation of heat loss is a very important function of mammalian skin. Being homoiothermous animals, with temperatures around 350C (rabbit 360C), their metabolism is regulated to work best at a particular temperature and therefore is must be constantly regulated. Production of heat is inevitable in every living cell, and is greatest in mammals in muscles and glands, particularly the liver. The heat is more or less equally distributed by the vascular system and regulated mainly by the skin. Heat is lost with any material passed out of the body; such, for example are the faeces, urine and exhaled air. But the greatest quantity of heat is lost by evaporation of sweat from the body itself. Therefore, talent heat necessary for this, comes from the body itself. Therefore regulation of the amount of sweat will mean regulation of heat loss. It is accomplished by control of the surface blood vessels, including those which supply the sweat glands. Vaso-dilator nerve fibres of the parasympathetic system stimulate enlargement of peripheral vessels, while vaso-constrictor fibres of the sympathetic system stimulate contraction. There is a centre in the brain which correlates these processes. Nerve endings in the skin are sensitive to a variety of stimuli which are commonly grouped together under the sense of touch. There are ending sensitive to mechanical contact, others for pain, and others for high and low temperatures.

Other special functions of the mammalian skin are those associated with special secretions such as milk and ear-wax, erection of the hair to present a more terrifying appearance to a rival or predator, and the shaking or movement of the skin for various purpose.

Lets now take a.deeper look into the functions of the mammalian skin

Functions of the Mammalian Skin

The skin is a protective barrier against mechanical impact and pressure, variation in temperature, microorganisms and radiation. It is also a reservoir for electrolytes, water, proteins, fat and vitamins.

During embryonic development the ectodermal covering progressively thickens, and fibroblasts (connective tissue cells) transform to a fiber-rich matrix. The underlying dermis consists of sweat glands, hair follicles, sebaceous glands and fat (a good insulator). Other specialized pelage structures include nails, claws and horns.

Enclosing Barrier

The skin is the body’s first barrier to external aggressions. It protects against mechanical impact and pressure, variations in temperature, microorganisms, radiation and chemicals. It also regulates several aspects of physiology including thermal regulation, moisture balance and vitamin D synthesis. The outer layer is a stratified nonvascular epidermis composed of flattened cells that are cornified to resist abrasion, and the innermost layer is the dermis composed of connective tissue and a rich supply of fatty oil (skin secretions). It attaches to underlying bone and muscle and supplies it with blood vessels and nerves. The underlying subcutaneous fat layer is not part of the skin and provides insulation.

In addition to its protective and regulatory functions, the skin is a sensory organ. It contains many nerve endings that can detect heat and cold, touch, pressure, vibration and tissue injury. These nerves send messages to the brain via the nervous system for processing and relaying the information to other areas of the body.

Hair is a common feature of mammalian skin that keeps the animal warm by trapping air close to the body. Feathers are another type of insulating appendage found on birds, which enables them to fly. The skin of reptiles is covered with hard protective scales that serve the same purpose. Hairs and scales contain keratin, which is a protein that gives the skin its strength and elasticity.

Some species of mammals have modified their pelage to serve other purposes in addition to protection and insulation. Fur and horns are examples of keratinized derivatives of the integument that have evolved for other functions like thermoregulation, sexual display and defense.

In addition to these specialized structures, most mammalian species have a variety of specialized color patterns that help them blend in with their environment. Examples range from the dappled muddy scales of vine snakes to the bright green of chameleons and the drab brown of antelope. Some, such as the chameleons and the octopi, can change their pigmentation at will, displaying a color pattern that matches whatever background they are against.

Environmental Protection by the Mammalian Skin

The outer layer of mammalian skin, the epidermis, provides a barrier function protecting mammals against environmental stresses, including physical, chemical and thermal stress as well as against loss of water. This layer is primarily made up of a multilayered epithelium consisting of the interfollicular epidermis (IFE) containing hair follicles, sebaceous glands and eccrine sweat glands as well as keratinocytes. The keratinocytes, in turn, form the stratum corneum of the skin which protects against sun damage and other external agents such as pathogens, viruses and toxins. Several cell types are present within the epidermis, including keratinocytes, Merkel cells and melanocytes. The latter two cell types produce the pigments that give the skin its color. The barrier is reinforced by a basement membrane that controls what can pass between the dermis and epidermis.

The skin also contains lymph and blood vessels that vascularise the epidermis. The surface of the skin is covered with papillae, which project into the epidermis to reinforce the epidermal-dermal interface. These papillae, together with hair follicles, are important sites for the production of protein, such as collagen, that contribute to the strength and resilience of the epidermis. The papillae also help to create the characteristic wrinkles of aged skin.

In addition, the skin contains sensory cells that respond to touch, heat and cold as well as a variety of other stimuli such as light, hormones and chemicals. The skin also serves as an important site for the synthesis of vitamin D, the production of melanin and the protection of essential fat-soluble vitamins and minerals. In addition, it serves to regulate body temperature and is a vital organ for endocrine regulation.

The skin is the largest organ of the integumentary system in humans with up to seven layers of ectodermal tissue guarding muscles, bones, ligaments and internal organs. The skin may appear hairy or glabrous (hairless). Mammalian skin is generally very tolerant of the environment and can cope with many conditions that affect other organs and systems. For example, severe burns and injuries to the epidermis can often heal without serious consequences as long as the underlying dermis remains intact.

Temperature Regulation by the Mammalian Skin

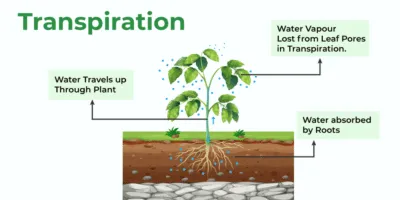

The skin helps keep body temperature within limits, even when environmental temperatures vary; this is called thermoregulation. The massive blood supply in the dermis (middle layer) of the skin aids this process, as dilated vessels encourage heat loss and constricted ones retain it. The evaporation of sweat is another important factor: water molecules cool the body by carrying heat away from its surface.

In addition, many animals store fat and other materials in the tissues of the skin to serve as extra insulation against cold. Some, such as elephants, develop thick layers of blubber that help to keep internal organs warm and to provide a protective barrier against predators.

Skin also provides an important sensory function: it is covered with a layer of flat hairs, or follicles, that are usually coated with pigments that give the animal its color. When these follicles are stimulated, they secrete a salty fluid called sebum that acts as an additional barrier against infection. In addition, the skin contains specialized cells, including keratinocytes, which cover the epidermis with an impenetrable barrier, Langerhans cells that are involved in immune response and melanocytes that produce the pigments that color the skin.

The underlying dermis also contains a basement membrane that restricts what can pass between it and the epidermis. In some species of mammals, such as rabbits and guinea pigs, this membrane is reinforced with a strong protein that forms a tough layer known as the cuticle. The cuticle provides a second protective barrier against damage and infections, but it also keeps the skin supple and healthy by maintaining its flexibility.

Finally, the epidermis contains a large number of nerve endings that respond to touch, pressure, pain and temperature (see somatosensory system). This skin is highly flexible and has considerable elasticity due to an extraordinary matrix of collagen fibers, microfibrils and elastin in the dermis, as well as a network of glycoproteins called proteoglycans.

The skin of certain groups of mammals, especially primates, is under complex muscular control, and it can be moved to communicate emotions. For example, the pattern of a lion’s mane or the fur of a hamadryas baboon is used to intimidate or warn other members of its species.

Secretions by the Mammalian Skin

The skin is the first physical barrier that shields the body from microorganisms, environmental pollution and mechanical injury. It regulates body temperature, gathers sensory information from the environment, stores water, fat and vitamin D, and secretes sweat and pheromones.

The vertebrate skin consists of a superficial nonvascular epidermis and an inner dermal corium that interlock via fingerlike projections (dermal papillae). The stratified epidermis contains many types of stem cells and serves as the interface between the organism and the external environment. The epidermis is a tough, cornified structure that resists abrasion and provides an efficient barrier against the environment.

Cells in the basal layer of the epidermis proliferate through mitosis and differentiate to become multinucleate keratinocytes. As they move up the stratum, keratinocytes form cell junctions between themselves and with other keratinocytes and bind to extracellular matrix proteins. As they rise through the stratum, keratinocytes produce keratin proteins and lipids that contribute to the formation of the extracellular matrix. They also produce and secrete a water-soluble substance called the acid mantle, which protects against infection by bacterial pathogens.

As the epidermis matures, it begins to develop specialized structures such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands. The morphogenesis of these epidermal appendages requires precise coordination between the epidermis and its underlying mesenchyme, which harbors other types of stem/progenitor cells.

Many species of vertebrates have evolved special characteristics for their skin to enhance its protective and sensory functions. Some mammals, for example, have long, insulating hairs that trap warm air close to the skin and allow mammals to keep their bodies warm in cold environments. Birds have feathers that serve a similar function, and fish and reptiles have hard, protective scales that grow from follicles in their skin.

Mammalian skin is remarkably versatile. It can vary in color, texture and thickness, and it is adapted to different environments and lifestyles. For example, the thick skin of elephants helps them withstand harsh conditions and the constant friction against their tusks. Some parts of the skin are smooth and bare, such as the palms of our hands and the soles of our feet. Other areas, such as the thighs and buttocks of some mammals, are covered with dense fat deposits known as blubber, which provide insulation and allow the animals to move with greater efficiency.